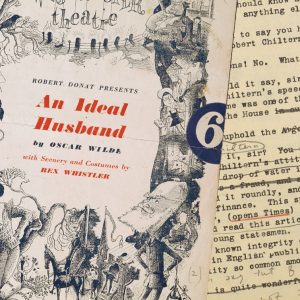

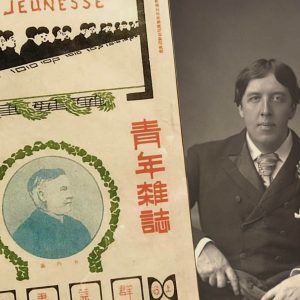

British Library to stage Oscar Wilde event at Hong Kong International Literary Festival, November 2018.

Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray

出版日期: 1890 文学时期: Victorian 类型: Gothic

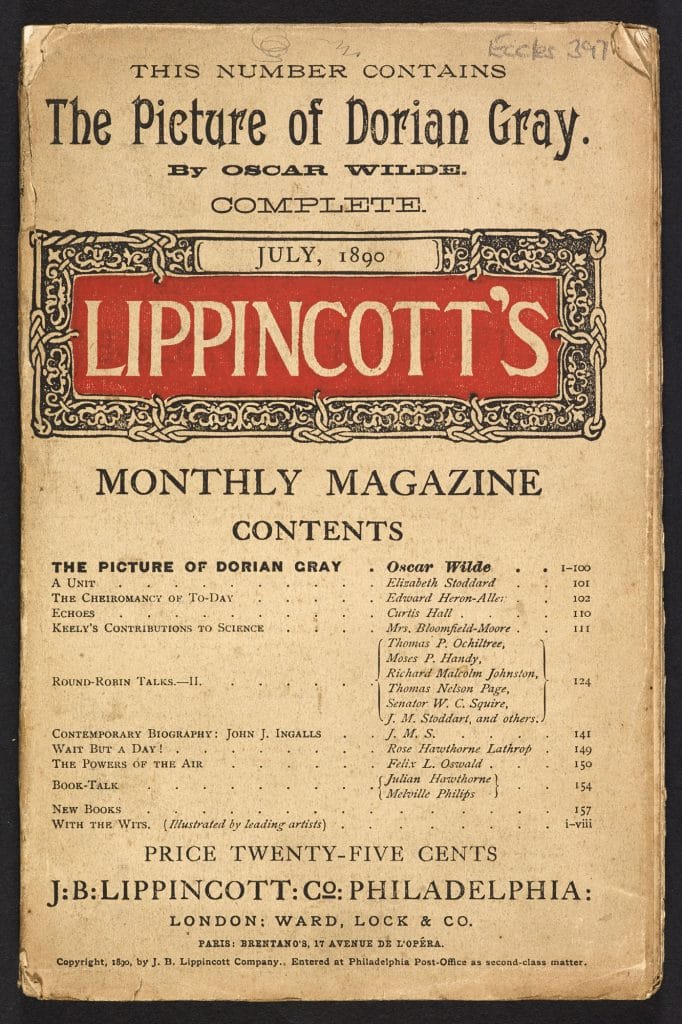

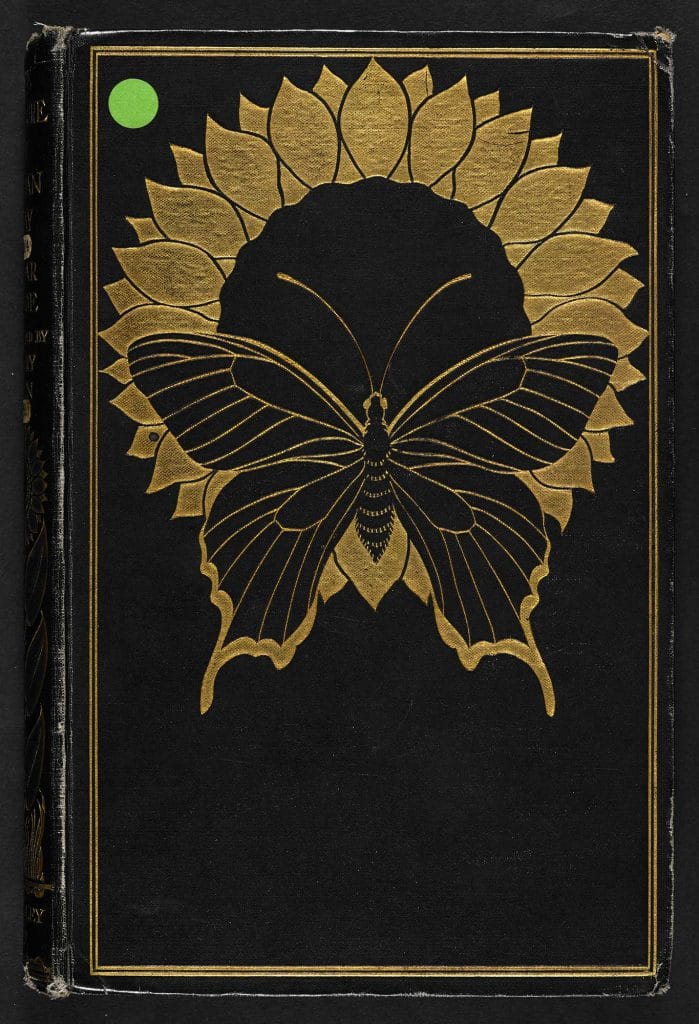

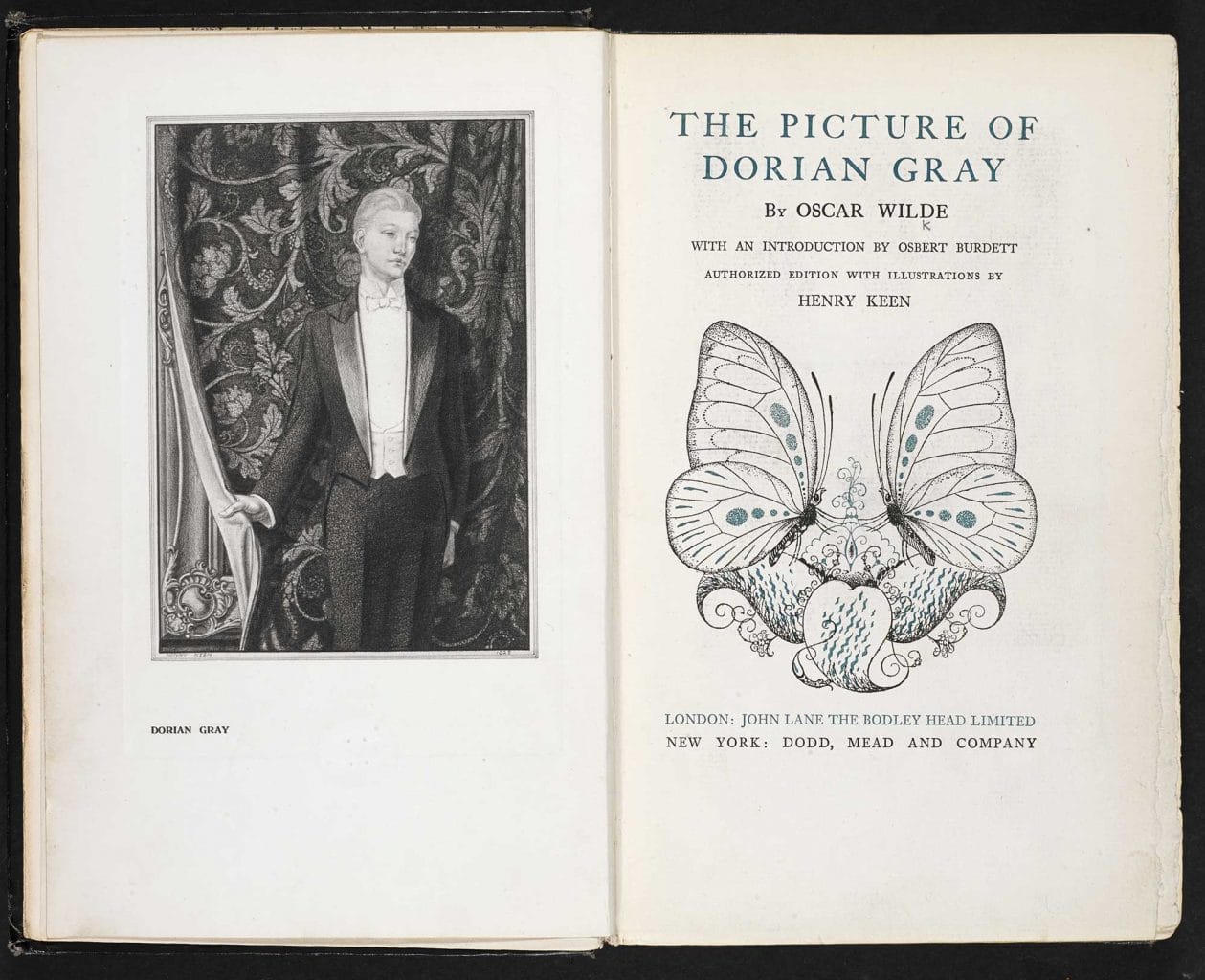

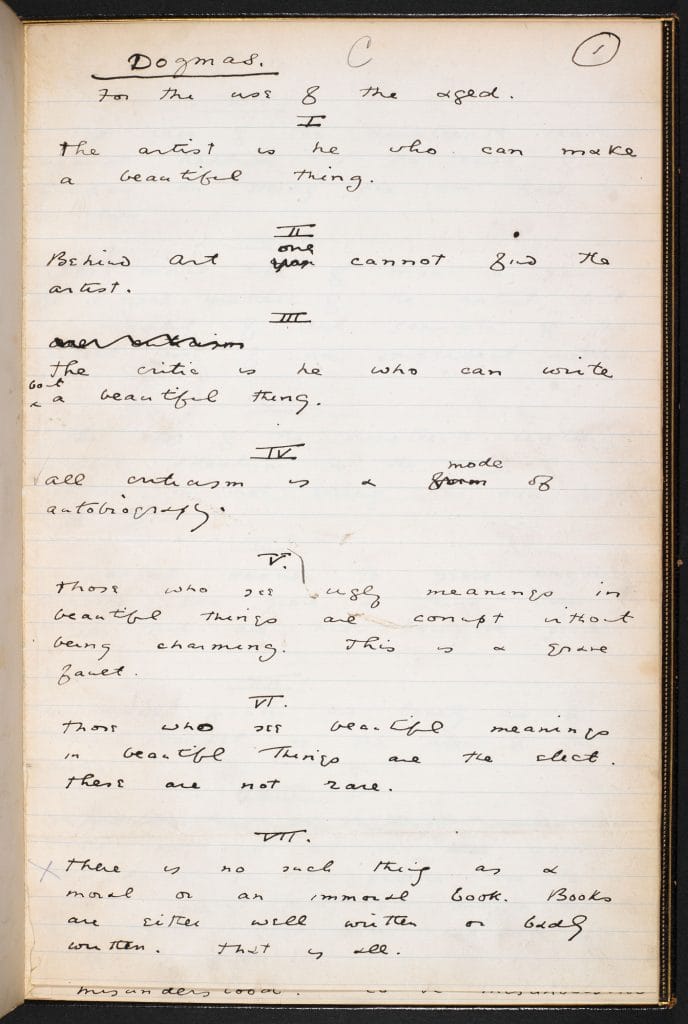

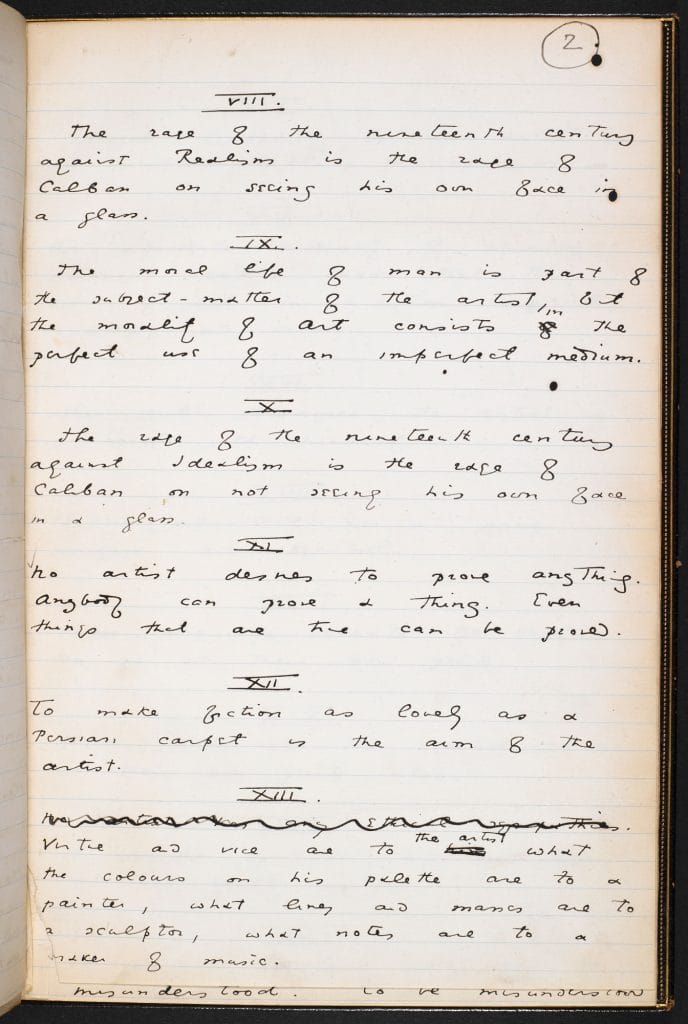

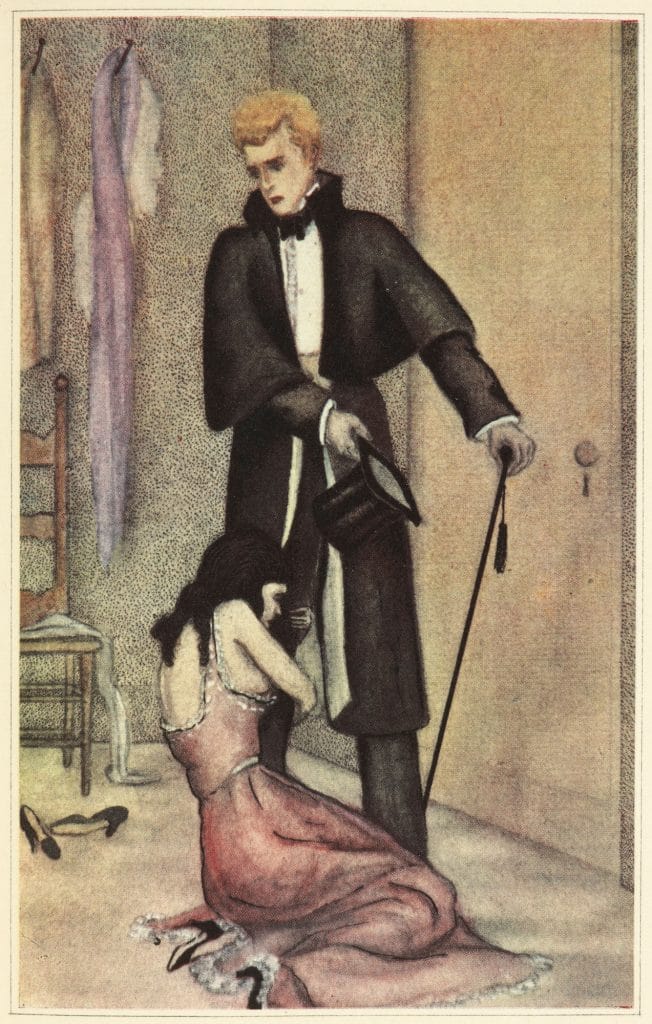

Oscar Wilde’s Gothic tale The Picture of Dorian Gray first appeared in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine in 1890. It was revised and expanded into a novel, which British bookseller W H Smith rejected as ‘filthy’. The book explores the doctrine of Aestheticism: devotion to hedonism, beauty and art for art’s sake. Dorian dedicates his life to decadence and sensuous pleasure; while he remains youthful, his portrait gradually ages and decays, reflecting the depravity of his actions. Some reviewers were repelled by the work, and Wilde’s wife, Constance, lamented, ‘no one will speak to us’. Many critics, however, have seen it as a moralistic tale in which the protagonist receives his just deserts. In the Preface the author declared: ‘There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all’.

The third of three animated virals to promote the new Sky series ‘Penny Dreadful’, created at Beakus by director Gergely Wootsch. Taking inspiration from the origins of Frankenstein, this dark and atmospheric clip is narrated by Matthew Sweet, and illustrates how the novel came about.

‘Penny Dreadful’ is a major drama series on Sky created by John Logan and starring Josh Hartnett, Timothy Dalton, Eva Green and Billie Piper. The animation was first released as an exclusive on Digital Spy.

The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) is a superb example of late-Victorian Gothic fiction. It ranks alongside Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) as a representation of how fin de siècle literature explored the darkest recesses of Victorian society and the often disturbing private desires that lurked behind acceptable public faces. The novel also examines the relationship between art and reality, highlighting the uneasy interplay between ethics and aesthetics as well as the links between the artist, his or her subject and the resulting image on canvas.

‘The terrible pleasure of a double life’

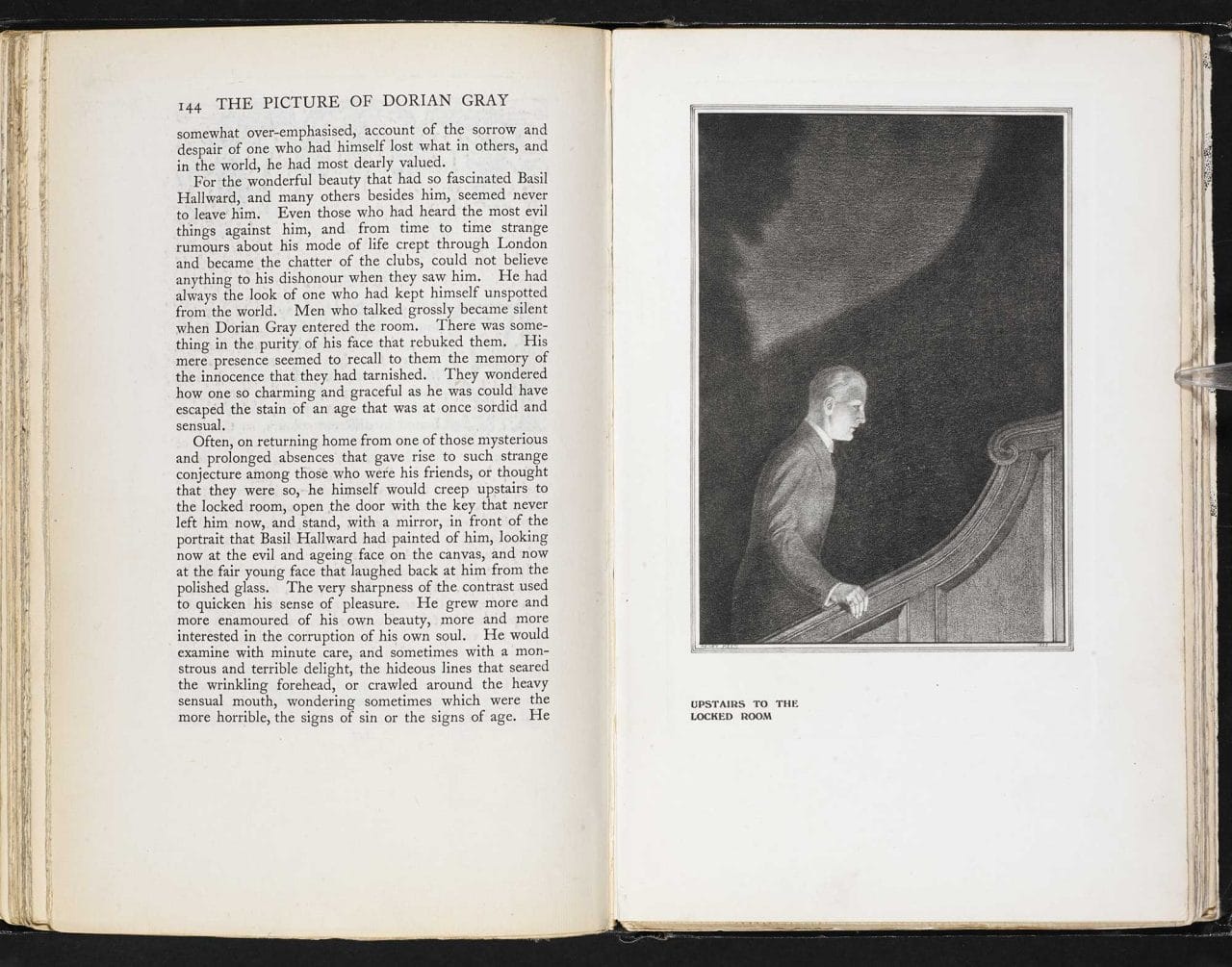

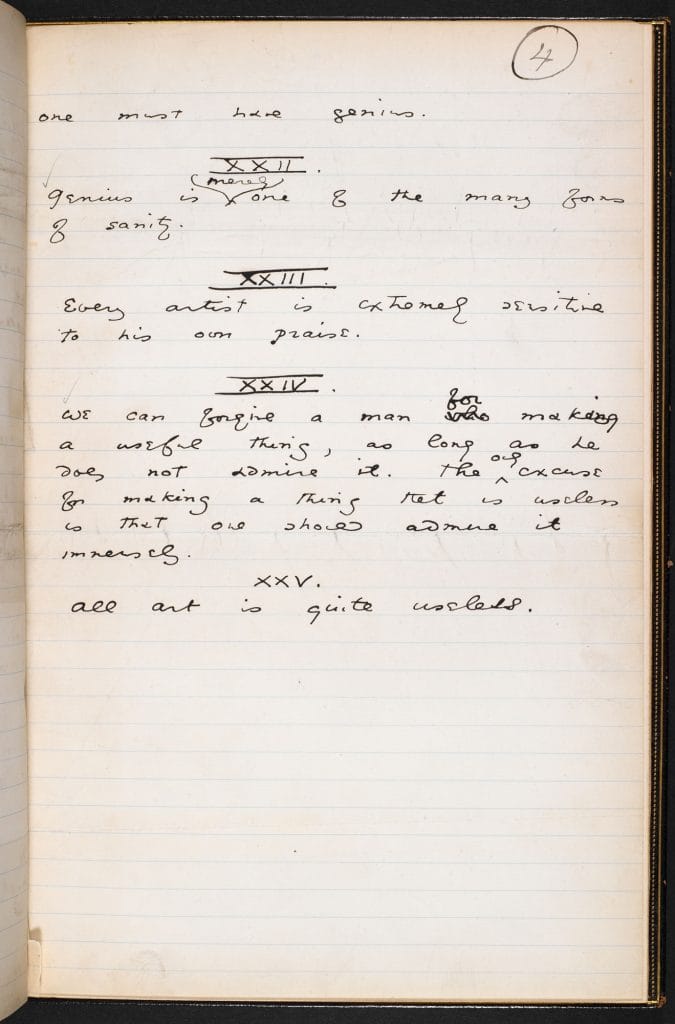

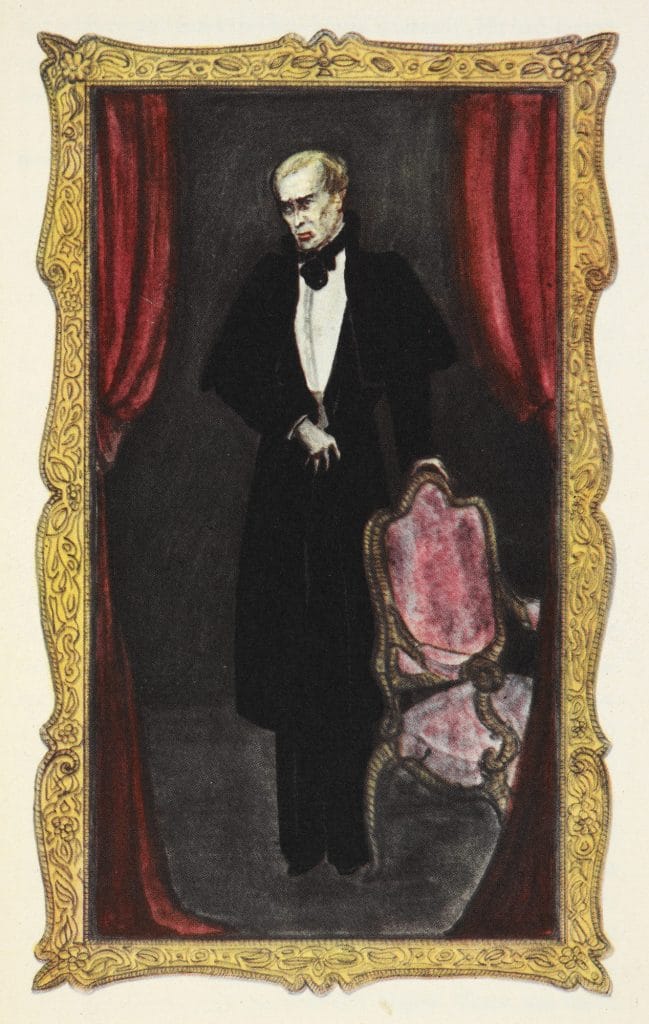

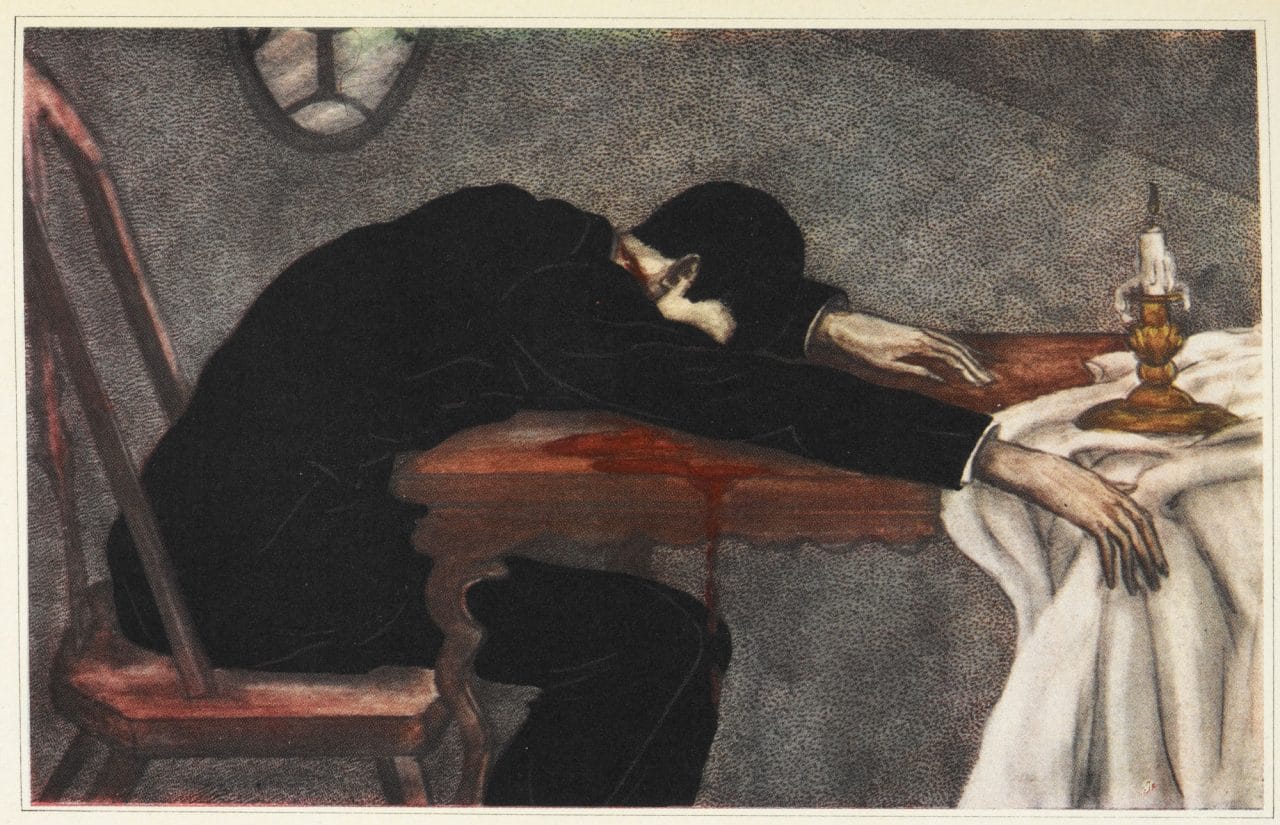

The Picture of Dorian Gray deals with the shadows between appearance and reality; between the surface people present to society and their hidden vices and desires. Dorian remains ever youthful no matter how vile his behaviour. Meanwhile, his portrait – an oil painting locked in the attic like a guilty secret – gradually decays, bearing every line of his debauchery as well as the ravages of time. Rather like Dr Jekyll in Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Dorian is able to pursue his decadent activities knowing his respectable appearance and unblemished looks will shield him from accusations of depravity. He can thus ignore the pious morality that pervades the society in which he lives. His ability to have the best of both worlds – the continued acceptance of his peers and the ability to fulfil his basest desires – drives his fascination with events. When attending a society gathering only hours after having committed a murder, we are told Dorian ‘felt keenly the terrible pleasure of a double life’ (ch. 15).

Dorian’s friend Lord Henry makes this link between the criminal and the respectable citizen clear when he observes: ‘Crime belongs exclusively to the lower orders. I don’t blame them in the smallest degree. I should fancy that crime is to them what art is to us, simply a method of procuring extraordinary sensations’ (ch. 19). Dorian, with his visits to opium dens and his delight in high culture, combines the criminal and the aesthete – the very definition of ‘decadence’ distilled into a single person, and a disturbing example of the split between the wholesome public persona and the furtive private life.

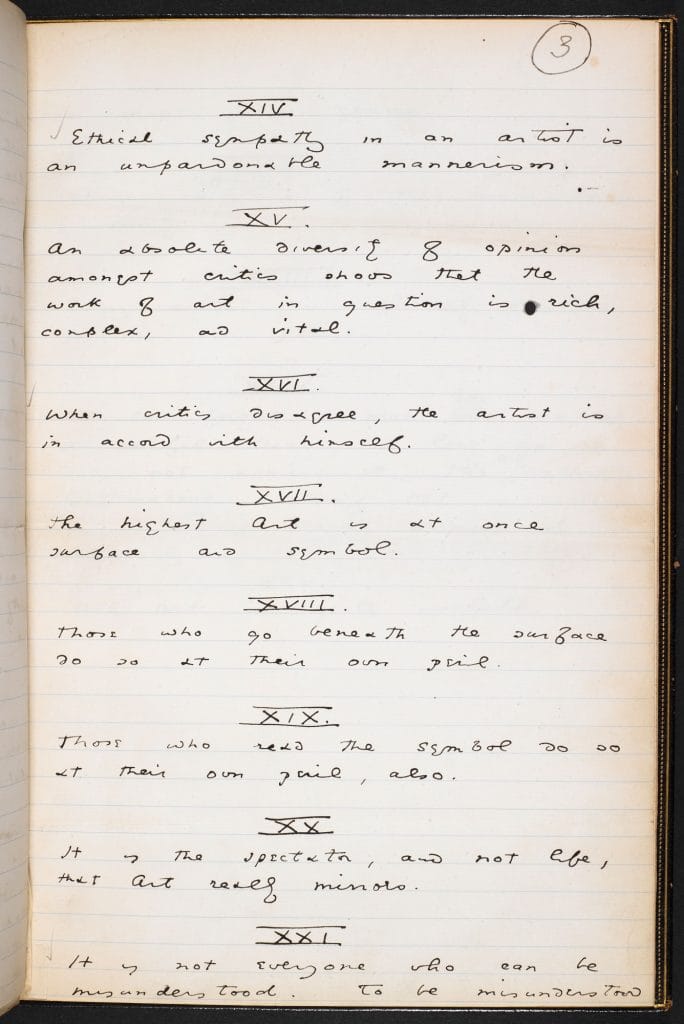

Ethics and aesthetics

While much of The Picture of Dorian Gray delights in the beautiful and the intoxicating indulgence of the senses – the novel’s opening paragraph, for example, describes the heady pleasures to be derived from the scents of roses and lilacs – it can be argued that Wilde intended his book neither as a celebration of decadence nor as a fable about the perils of its excesses. As Wilde states in the Preface to the novel, ‘There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all’. In other words, any moral disgust or vicarious pleasure derived from the book reflects more upon us as readers than it does on the novel itself. The book is a tale, pure and simple. It is we, the readers, who force it to bear the weight of a moral dimension.

The idea lying behind Aestheticism, the controversial theory of art that was newly fashionable at this time, was that art should be judged purely by its beauty and form rather than by any underlying moral message (‘art for art’s sake’). This is exemplified in the novel by the dandyish Lord Henry Wotton. Lord Henry advocates the hedonistic pursuit of new experiences as the prime objective in life. In his view, ‘one could never pay too high a price for any sensation’ (ch. 4). Dorian, although seduced by Wotton’s poisonous whisperings, is increasingly interested in the moral consequences of his behaviour. He stands before his decaying portrait, comparing the moral degradation as depicted in oil with his unblemished innocence as reflected by the mirror. The contrast gives him a thrill of pleasure: ‘He grew more and more enamoured of his own beauty, more and more interested in the corruption of his own soul’ (ch. 11). Dorian – via his wish to remain handsome, while the painting bears the weight of his corruption – muddies the boundary between art and life, esthetics and ethics. The painting is made to serve a moral purpose, being transformed from an object of beauty into a vile record of guilt, something ‘bestial, sodden and unclean’ (ch. 10). This tainting of the picture perhaps constitutes, for the aesthete, Dorian’s greatest crime – namely the destruction of a beautiful artwork.

Paintings and ancestry

Paintings often play a sinister role in Gothic fiction. The first Gothic novel, Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), includes a figure stepping from a painting into reality, while Melmoth the Wanderer (1820), written by Oscar Wilde’s great-uncle Charles Maturin, describes the haunting gaze of a portrait as it follows the viewer around a room. The picture hidden in Dorian’s attic may be the most disturbing portrait in Wilde’s book, but it is not the only canvas in the novel which provides a pointer to Dorian’s behaviour. At one point Dorian walks through the picture gallery of his country home, looking at the portraits of his ancestors: ‘those whose blood flowed in his veins’. The saturnine and sensuous faces stare back at him, causing Dorian to reflect whether ‘some strange poisonous germ crept from body to body till it had reached his own?’ (ch. 11). This poses the question as to whether Dorian is free to determine his own actions, and is thus entirely responsible for his behaviour, or whether his actions are dictated by his genetic inheritance – an inheritance, as the faces of his ancestors indicate, ‘of sin and shame’. The eminent mental pathologist Henry Maudsley wrote in his book Pathology of Mind (1895): ‘Beneath every face are the latent faces of ancestors, beneath every character their characters’. This idea already seems present in much Gothic fiction, including Wilde’s novel.

The Picture of Dorian Gray provides both a standard ‘Gothic’ account of Dorian’s actions – the supernatural picture and the lascivious ancestors gazing from their portraits – but also a forward-looking scientific rationale for his depraved desires, namely the importance of genetic inheritance in determining behaviour. Dorian resembles his mother physically, inheriting from her ‘his beauty, and his passion for the beauty of others’ (ch. 11), while, as his corruption accelerates, the twisted portrait in Dorian’s attic increasingly resembles his wicked grandfather. This latter idea suggests Dorian is a scientific case study, as well as a moral one. Throughout the book Lord Henry treats Dorian as a beautiful subject upon which to experiment, partly via his encouragement of Dorian to pursue a philosophy of pleasure, and partly through a call to social revolution – a wish to abandon the restraints of Victorian morality on the grounds that sin and conscience are outmoded primitive concepts to be swept aside in the pursuit of new sensations. Lord Henry locates progress in the overcoming of hereditary fears: ‘Courage has gone out of our race … The terror of society, which is the basis of morals, the terror of God, which is the secret of religion – these are the two things that govern us’ (ch. 2). His call to youth is a call to courage. Dorian’s ultimate failure to live up to Lord Henry’s ideals is due to his inability to escape his conscience as depicted in the portrait. By attempting to destroy the painting, and thus free himself from the constant reminder of his own guilt he, ultimately, manages only to destroy himself.

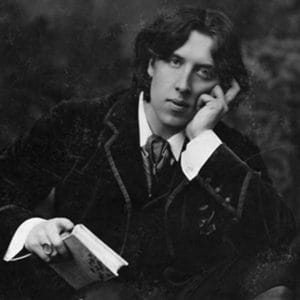

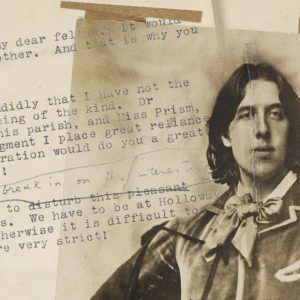

Oscar Wilde and Dorian Gray

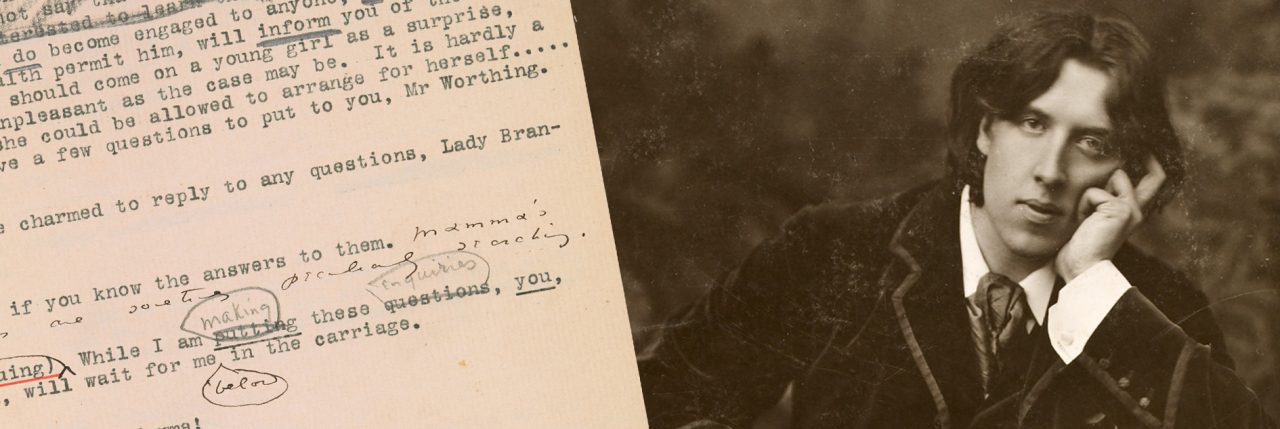

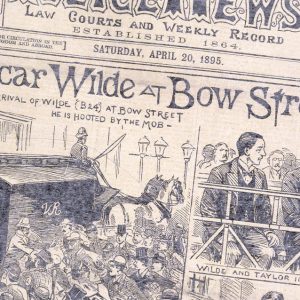

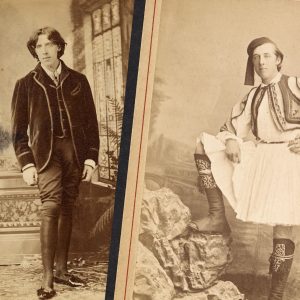

The Picture of Dorian Gray first appeared in the July 1890 number of Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine and immediately caused an outcry due to its perceived references to homosexual desire. The review in the Scot’s Observer memorably described the book as having been written for ‘outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph-boys’ – a reference to a recent scandal involving a homosexual brothel in London’s Cleveland Street. In response to such hostile criticism Wilde considerably amended the text, and a longer, noticeably ‘toned-down’ version of the book was published by Ward Lock and Co in April 1891. It is this later version that forms the standard text of the novel. Even so, the Lippincott’s version was used by opposing counsel in evidence against Wilde in two of his trials in an attempt to show him guilty of ‘a certain tendency’. For many people Oscar Wilde the artist – with his flamboyant public persona and his secretive private life – and his novel with its two distinctly different versions and its duplicitous central character mirrored each other from the start.

Written by: Greg Buzwell

Greg Buzwell is Curator of Contemporary Literary Archives at the British Library. He has co-curated three major exhibitions for the Library – Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination; Shakespeare in Ten Acts and Gay UK: Love, Law and Liberty. His research focuses primarily on the Gothic literature of the Victorian fin de siècle. He has also edited and introduced collections of supernatural tales by authors including Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Edgar Allan Poe and Walter de la Mare.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License